Beginning, middle & end

12 March - 23 April 2005

Jenna Collins

Every narrative moves from its beginning to a middle and a conclusive end. Usually. The artists in this show offer narratives that are far from complete, in which we are unsure at what point we have entered the story’s timeline, beginning, middle or end.

On the ground floor and throughout the stairwells, Matthew Richardson’s groupings of objects and gestures imply associations or meanings, through their very particular choice and arrangement. Through their juxtapositions Richardson makes, the significance of one object is altered by another. The Statue of Liberty is dwarfed by a human hair (or the hair is made giant by the statue); an arbitrary date in the future becomes significant by our personal reading of, or association with it. There is significance to the found objects he uses, as well as an element of chance. Each object has been removed from its role in everyday life at a precise moment of incidence. The scratches and scuffs of wear and tear are preserved as a testament to the objects’ other lives, outside of the art institution. Richardson has applied this to the gallery itself, where his preservation of a scorched wall betrays the scene of a fire. Once the show finishes, the works revert to their everyday use. The owl’s perch becomes a functional broom in the artist’s kitchen; the scorched wall becomes an anonymous blank space once again.

On the first floor, Karla Williams’ series of video tableaux, Anti Chambers, is the epilogue to a series of domestic episodes, a glimpse of something unseen that has just taken place moments before. We can only guess what has led to these deserted scenes. Perhaps the swinging light and door chain denotes someone’s departure. Could the wheelchair have been tipped accidentally or deliberately? Each vignette is set in a different hallway, For Williams, these epitomise a non-space or synapse between public-private, and fact-fiction; a space where undisclosed captivation is met with potential autonomy. The scenes play out before us but we never see the protagonists or understand what has gone before.

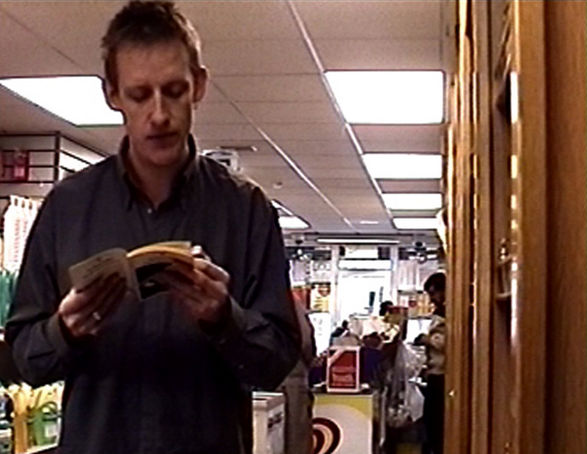

In Certain Private Conversations, Jenna Collins strips the narrative even more extremely. The piece presents a reading of stage directions from the play Death of A Salesman, delivered by a professional actor in a Manchester newsagents. Arthur Miller’s play is a tale of a man unable to reconcile the reality of his mediocre life in late 1940s America with the post-war capitalist American dream. Crucially lacking any dialogue, the play is rendered a barely recognisable abstraction. Initially, the actor gives the most prominent performance, but soon the severely abbreviated text, noisy machinery and shop staff unwittingly upstage him in turn. By presenting a fragmented story in the newsagents, a location with its own inherent narratives, Collins recklessly leaves the viewer to create a third narrative from the events.

These are partial stories, incomplete sentences that require us to fill in the missing words, allowing us to speculate on what has already passed or is yet to come. Together the works in this exhibition disrupt the straight line of the narrative, presenting observations and fabrications that form beginnings, middles and ends, but not necessarily in that order.

- The following Artists were in this show:

- Jenna Collins

- Matthew Richardson

Programme

- 2025

- 2024

- Workshop: Aqsa Arif 16 November

14.00-16.00, Weaving Our Histories Through Fabric - Talk:

Stephen Sutcliffe 18 October

The event is free, Friday 18th October, 6pm - 8pm, and there will be refreshments and a chance to see what has been happening on UNITe 2024 so far. - Gwaith x g39: Potluck Cinema 4 October

- Cinema: The Film London Jarman Award 2024 3 October

Larry Achiampong, Maeve Brennan, Melanie Manchot, Rosalind Nashashibi, Sin Wai Kin, Maryam Tafakory - All day screening in the g39 Cinema // Trwy`r dydd mewn sinema g39 - Talk:

Larry Achiampong 3 October

Join us for the talk, have a drink, see UNITe 2024, have a chat. Thursday 3rd October, 6pm - 8pm. Free. Everyone is invited! // Ymunwch â ni ar gyfer sgwrs i gael diod, gweld UNITe 2024, a chael sgwrs. Am ddim. Mae croeso i bawb! - Social: Neighbourhood Crowd 28 September - 26 October

- UNITe 2024 18 September - 26 November

Jessica Horsley, Rhys Slade Jones, Esyllt Lewis, Sophie Lindsey & Sophie Mak-Schram & Amy Treharne - Listening Session: Paul Nataraj + Alliyah Enyo 6 September

17:00-19:00 - `HANDLE WITH CARE` In Conversation:

Che Applewhaite & Olukemi Lijadu 5 September

Che is part of Jerwood Survey III, open until 07/09/24. - Talk:

Sam Keelan 9 August

Join us for the talk, have a drink, see the show, have a chat. Free. Everyone is invited! // Ymunwch â ni ar gyfer sgwrs i gael diod, gweld yr arddangosfa, a chael sgwrs. Am ddim. Mae croeso i bawb! - Cinema:

Threshold

& BSL Tour of SURVEY III 2 August

Hosted by // A gynhelir gan Jonny Cotsen - Jerwood Survey III 13 July - 7 September

Che Applewhaite, Aqsa Arif, MV Brown, Philippa Brown, Alliyah Enyo, Sam Keelan, Paul Nataraj, Ciarán Ó’Dochartaigh, Ebun Sodipo and Kandace Siobhan Walker. - cinema:

Thomas Abercromby

J O H N 21 June

All g39 events are free, doors open at 6pm, there are refreshments. The OPEN exhibition & The Healing Project is also open. // Mae holl ddigwyddiadau g39 am ddim, drysau yn agor am 6yh, mae lluniaeth. Mae`r arddangosfa AGORED & The Healing Project hefyd ar agor. - Exhibition: The Healing Project 8 - 22 June

Abeer Ameer, Nasima Begum, Yanti Hashim, Sweeta Hasmi, Husna Hossain, Ayesha Ibrahim, Samar Iqbal, Jaffrin Khan, Anjuman Khanom, Neda Muhammad, Hanan Sandercock - OPEN Exhibition 2024 8 - 22 June

- Corrina Eastwood

The Baby And The Snake 3 May - Gypsy Makers 10 April - 25 May

Daniel Baker, Rosamaria Kostic Cisneros, Artur Conka, Corrina Eastwood, Cas Holmes, Billy Kerry, Shamus McPhee & Dan Turner - Cinema Programme: Betwixt 16 March

- Gallery 2 // Galeri 2:

We Ran Together 10 February - 23 March

Durre Shahwar - Michal Iwanowski - George H. Wale - Exhibition:

Here, at the edge, today. 27 January - 23 March

Zara Mader, Gail Howard, Adele Vye, Sadia Pineda Hameed & Beau W Beakhouse & Phoebe Davies. - Gallery Intern - g39 10 January - 13 February

- Workshop: Aqsa Arif 16 November

- 2023

- Talk // Sgwrs: Beatriz Lobo 14 December

Free // Am ddim. 14/12/23, 18.00-20.00 The talk will start at 18.30 // Bydd y Sgwrs yn dechrau am 18.30 - Talk // Sgwrs:

Emma Hart 29 November - Cinema // Sinema: Jarman Film London 2023 screening 10 November

Ayo Akingbade - Andrew Black - Julianknxx -

Sophie Koko Gate - Karen Russo - Rehana Zaman - Talk // Sgwrs:

Andrew Black 10 November - Gallery // Galeri:

We Ran Together - Richard Billingham 27 October - 16 December - Cinema: Fake Your Death,

Take a Seat 16 September

Mae g39 yn falch o groesawu Fake Your Death, Take a Seat - y trydydd mewn cyfres o ddangosiadau ffilm wleidyddol rhad ac am ddim sy`n cael eu cynnal ledled Caerdydd. // g39 is proud to host Fake Your Death, Take a Seat - the third in a series of free political film screenings taking place across Cardiff. Picking up the baton from @dyddiaudu - Publication Launch:

No Time to Plan an Ending 7 September

Publication Launch - 1-2-1 sessions 31 August - 2 September

- Shelter Auction 30 August - 2 September

- Cinema - Jitterbug by Ayo Akingbade 18 August

Ayo Akingbade’s Jitterbug marks the rising London filmmaker`s thirteenth short film and continues her exploration into the city’s rapidly changing landscape. // Mae Jitterbug gan Ayo Akingbade yn nodi trydedd ffilm fer ar ddeg y gwneuthurwr ffilmiau addawol o Lundain, ac mae’n parhau â’i harchwiliad i dirwedd y ddinas sy’n prysur newid. - Talk: Priyesh Mistry 27 July

- Open table 23 July - 25 August

- Derek Jarman - Blue 15 July

Screening // Sgrinio - madeinroath Open Exhibition 2023 14 July - 12 August

- (Team) Work in Practice: Jerwood Toolkit Workshop 7 July

- Performance: SCORE 1 July

- Intervention: Teddy Hunter and Imogen Marooney 1 July

Live performance // Perfformiad yn fyw - On Your Face Collective Queer Short Films 30 June

- Cinema:

Mauve, Jim and John

Paul Maheke 30 June

Mauve, Jim and John is part of The Artangel Collection. // Mae ‘Mauve, Jim and John’ yn rhan o The Artangel Collection. - Workshop: SSAP at Refugee Week 2023 24 June

Donations on the door. - Library Residency: Joshua Jones 16 June - 16 July

- COMMONPLACE 16 June - 3 September

g39 Summer Season - In The Same Breath 20 May

All day sgreening - sinema drwy`r dydd - Burning Things 19 May

All day sgreening - sinema drwy`r dydd - Soft split the Stone 8 April - 20 May

Philippa Brown, Aled Simons, Tom Cardew, Alice Briggs, Rebecca Jagoe - Pave Your Path:

Open Call // Galwad Agored 20 - 31 January

Career-focused Workshops for Moving Image Artists

g39 is pleased to be collaborating with Film London and Videotage, Hong Kong, to invite six Welsh or Wales based early career artists to apply to the Pave Your Path programme. The programme will support moving image artists who are working to build their careers in the art sector. - One-to-One sessions for artists:

Paddy Gould + Roxy Topia 13 - 14 January

Start the year off with some valuable creative conversations. We’ve got Roxy Topia and Paddy Gould visiting Cardiff to do 1-2-1s at g39. // Dechreuwch y flwyddyn gyda rhai sgyrsiau creadigol gwerthfawr. Mae Roxy Topia a Paddy Gould yn ymweld â Chaerdydd i wneud sesiynau un-i-un yn g39.

- Talk // Sgwrs: Beatriz Lobo 14 December

- 2022

- Workshop:

Situated Psychogeography - Delphi Campbell 3 December

14.00-16.00 - Workshop:

Zine-making with Delphi Campbell 26 November

14.00 - 16.00 - Gallery:

Aildanio 19 November - 17 December

Farah Allibhai, Lia Bean, Leila Bebb, Candice Black, Arty Jen-Jo, Deborah Dalton, Paddy Faulkner, Clarrie Flavell, Rebecca F Hardy, Emily-Jane Hillman, Jacqueline Janine Jones, Cerys Knighton, Ruben Lorca, Jo Munton, Roz Moreton, Ceridwen Powell, Gaia Redgrave, Tina Rogers, Menai Rowlands, Jordan Sallis, Booker Skelding, Bethany & Linda Sutton, Alana Tyson, Phillippa Walter, Sara Louise Wheeler, Julia Wilson. - Talk//Sgwrs:

Fran Flaherty & Ruth Fabby 19 November

10.30-12.00 Breakfast Club/Gallery Talk with exhibition selectors // Clwb Brecwast/Sgwrs Oriel gyda detholwyr arddangosfeydd - Talk//Sgwrs: Jay Bedwani 28 October

- Talk // Sgwrs: Grace Ndiritu 26 October

Talk // Sgwrs (IRL and Zoom, blended event) 26/10/22, 18.00-19.30 - Talk // Sgwrs - Gypsy Maker 5 24 October

Imogen Bright Moon, Corrina Eastwood & Dr Daniel Baker - Cinema:

The 2022 Jarman Award // Gwobr Jarman 2022 21 October

Jamie Crewe - Onyeka Igwe - Grace Ndiritu - Morgan Quaintance - Rosa-Johan Uddoh - Alberta Whittle - Cinema:

Selected 12 20 October

Sarah Gonnet - Sophie Hoyle - Jessy Jetpacks - Seo Hye Lee - April Lin 林森 - Laura Lulika - Jennifer Mehigan - Ker Wallwork. - Talk//Sgwrs: Machynys Forgets Itself - Tom Cardew 21 September

- Gallery:

Kathryn Ashill - Principal Boy 17 September - 29 October

Kath Ashill Ft. Len Blanco & Megan Winstone - Heavy Water Collective

- residency 4 - 10 July

Victoria Lucas, Joanna Whittle & Maud Haya-Baviera - tibrO yalP 1 July - 20 August

- g39 Fellowship FOUR 1 April - 0 January

Zara Mader, Phoebe Davies

Gail Howard, Adele Vye

Sadia Pineda Hameed & Beau Beakhouse. - UNITe22 9 March - 14 May

George Hampton Wale, Adam Moore, Zillah Bowes,

Gwenllian Davenport & Umulkhayr Mohamed - Dolly Sen - Broken Hearts for the DWP 3 March

A screening and Q&A with //

Sgriniad a sesiwn holi ac ateb gyda:

Dolly Sen & Caroline Cardus - madeinroath

Open Exhibition 2022 2 - 5 March

MiR warmly invites you to submit work for this year’s Open Exhibition, which, after a two year hiatus, we are delighted to announce will be at g39 in March 2022. Mae MiR yn eich gwahodd i gyflwyno gwaith ar gyfer yr Arddangosfa Agored ym mis Mawrth 2022, ac yn dilyn seibiant o ddwy flynedd rydym yn hynod falch o gyhoeddi mai g39 bydd y lleoliad eleni.

- Workshop:

- 2021

- Cekca Het:

Trans Panic:

Rhiannon Lowe:

Burn It Down

10 December

18.30 - 20.00 drop in. - Freya Dooley

Temporary Commons 3 December

11.00-17.00. Screenings on the hour, Dur. 43 minutes - A Call-Out for Trustees -

g39 needs your help. 3 December - 28 January

g39 needs your help.

Mae angen eich help ar g39 - Talk // Sgwrs:

Adham Faramawy 11 November - The 2021 Film London

Jarman Award Touring Programme 11 November

Larry Achiampong, Sophia Al-Maria, Jasmina Cibic, Adham Faramawy, Guy Oliver, Georgina Starr. - No

Time

To Plan

an Ending

16 October - 18 December

Becca + Clare, Freya Dooley, Rebecca Gould,

Rhiannon Lowe, Will Roberts, Neasa Terry - Workshop:

Nicolaas van de Lande

10/09/21 10 September

Artist-led Shape-shifting - Artes Mundi Screenings:

Carrie Mae Weems 4 September

Constructing History: A Requiem to Mark the Moment, 2008 Dur:20’04’’ & The Baptism, 2020 Dur:11’35’’ - Talk // Sgwrs:

Heather Phillipson

& Holly Davey 20 August - Artes Mundi Screenings:

Dineo Seshee Bopape 20 August

Title unknown at time of publication, 2018. Dur. 33’40” - Artes Mundi Screenings:

Meiro Koizumi 17 August

AntiDream #2 Torch Ritual Edit, 2021 , Dur: 28’00’’ - Talk // Sgwrs:

Rebecca Moss

& Mel Brimfield 12 August - Intermission: mwnwgl 1 August

- Florence Boyd -

What’s it worth?

valuing opportunities. 30 July - Shaun James:

Gallwch Argraffu Sgrin //

You Can Screen Print 30 July

Shaun James has put together this series of screen printing training videos. // Mae Shaun James wedi rhoi at ei gilydd cyfres o fideos hyfforddi argraffu sgrin. - Artes Mundi Screenings:

Beatriz Santiago Muñoz 25 July

La Cueva Negra, 2012. 20’00” & La cabeza mató a todos, 2014. Dur: 07’30” - Talk // Sgwrs:

Libita Sibungu 24 July - SURVEY II 3 July - 11 September

Saelia Aparicio, Tereza Červeňová, Sadé Mica, Rebecca Moss, Cinzia Mutigli, Katarzyna Perlak, Shenece Oretha, Tako Taal, Nicolaas van de Lande, Angharad Williams - The Male Graze - Guerrilla Girls 18 June - 18 July

Art Night 2021: Nothing Compares 2 U - Jerwood UNITe 2021 Open Studios 3 - 5 June

Gweni Llwyd - Wendy Short - Gwenda Evans - Beau Beakhouse & Sadia Pineda Hameed - Yewande YoYo Odunubi - Talk // Sgwrs: Katrina Palmer 28 May

- Simon Fenoulhet - How do I go Public? 14 May

G39 artist Resources // Adnoddau artist g39 - Gaia Redgrave - Kindness 14 May

G39 artist Resources // Adnoddau artist g39 - Talk // Sgwrs: Tai Shani 6 May

We are really pleased to host Tai Shani for an online talk this Summer. Thursday 6th May 2021, between 6-8pm - nonsequences 3 - 27 March

Kelly Best, Jennifer Taylor, Ian Watson, Fern Thomas. - Finding Aarti 12 February - 1 March

Intermission - Radha Patel - g39 Fellowship THREE 1 January - 0 January

Rebecca Jagoe, Aled Simons,

Alice Briggs, Philippa Brown

and Tom Cardew.

- Cekca Het:

- 2020

- Madam Kamboulé

Adéọlá Dewis 18 December - 1 March

Intermission - Adéọlá Dewis - Request Stop 11 December - 1 March

Intermission - Sarah Jenkins - The Value of Housework 27 November - 1 March

Intermission - Nasima Begum - Talk:

Michelle Williams Gamaker 15 October

19.00-21.00 -

Zoom event via

Eventbrite below - The 2020 Film London Jarman Award 14 - 15 October

Michelle Williams Gamaker, Jenn Nkiru,

Hannah Quinlan and Rosie Hastings,

Project Art Works, Larissa Sansour,

Andrea Luka Zimmerman - Talk: Gypsy Maker 4 - Cas Holmes & Dan Turner 30 September

Online event with Isaac Blake and Daniel Baker 6-8pm //

6-8yp Digwyddiad ar-lein gydag Isaac Blake a Daniel Baker. - Rosalie Schweiker - Artist Talk 21 June

Hosted by g39 and the artist on Zoom - We are still here // Rydyn ni dal yma 28 March - 28 July

- RAT TRAP x g39 22 February - 29 March

Aled Simons, Carlota Nóbrega, Cybi Williams, Dylan Huw, Elin Meredydd, Ella Jones, Gweni Llwyd, Hugo - Intermission 2020 0 January - 1 March

Adeola Dewis - Aled Simons - Aurora & Nasima Begum

mwnwgl - Rabab Ghazoul - Radha Patel - Sarah Jenkins - Noson Calan Gaeaf

w/ Aled Simons and friends 0 January

Intermission

- Madam Kamboulé

- 2019

- UNITe 2019 25 October - 21 December

Daniel Clark ~ Mylo Elliott ~ Sophie Lindsey ~ Natasha MacVoy Amber Mottram ~ Manon Parry ~ Radha P - g39 Fellowship TWO 25 September - 25 June

g39 Fellowship – Year Two Artists Announced - Sprung Spring 10 August - 12 October

Tim Bromage - Philippa Brown – Marcos Chaves - Rebbeca Gould - George Manson - Nightshift Internat - Rumblestrip 4 May - 13 July

Emanuel Almborg / Paul Eastwood / Nooshin Farhid James Moore / Paula Morison / Jessica Warboys - Love Hangover 4 May - 13 July

- g39 Fellowship - ONE 1 April - 0 January

- Survey 2 February - 0 January

- UNITe 2019 25 October - 21 December

- 2018

- 2017

- 2016

- Freya Dooley - Rhythms and Disturbances 22 October - 17 December

UNIT#1 - S Mark Gubb – Revelations: The Poison of Free Thought, Prt II

Mike Kelley – Mobile Homestead 22 October - 17 December - Noëmi Lakmaier - Cherophobia 7 - 9 September

- does that include us? / yn cynnwys ni? part 2 3 - 24 September

Part two SARGY MANN see more > see different > see better - UNIT#1 Carl Slater - Miss America’s Trip to Technoland 23 July - 20 August

- does that include us? / yn cynnwys ni? Part 1 23 July - 20 August

- Just Between Us 28 May - 25 June

Thomas Williams/ g39/ The Trinity Centre - Sticky little touchstones called plans 1 May - 1 June

- UNIT#1 Sam Basu and Kelwin Palmer 15 April - 12 May

The Project of Art: Aldo Rossi - Thomas-Irvine: Limen Locale 15 April - 25 June

- UNIT(e) 2016 13 January - 19 March

- Freya Dooley - Rhythms and Disturbances 22 October - 17 December

- 2015

- 3-Phase Georgie Grace 14 November - 12 December

Jerwood Encounters: 3-Phase - ISLAND III - Native 3 October - 12 December

- 3-PHASE Kelly Best 3 - 30 October

- ISLAND 4 July - 12 September

- Unit#1 Simon Fenoulhet: Underground 16 May - 13 June

- Unit#1 Ben Lloyd: The Road To New York 11 April - 2 May

- The Starry Messenger 11 April - 13 June

- UNIT(e) 2015 15 January - 14 March

- 3-Phase Georgie Grace 14 November - 12 December

- 2014

- Unit#1: Siân Melangell Dafydd – Foxy 15 November - 13 December

- Carwyn Evans: UDO 4 October - 13 December

- Unit#1: Inga Burrows - Offset 4 October - 1 November

- Reflections Towards a Well-tempered Environment

Part two:

Ship`s Biscuit 3 October - 9 November

Alex Rich - Cardiff Contemporary 2014 - Reflections Towards a Well-tempered Environment

Part three:

A Flare for a Horn 3 October - 9 November

Alex Rich - Cardiff Contemporary 2014 - Reflections Towards a Well-tempered Environment

Part one:

HIDE 3 October - 9 November

Alex Rich - Cardiff Contemporary 2014 - Cities of Ash 12 July - 13 September

- If This Is Nowhere 12 July - 13 September

Work by Tom Crawford and associated programme - Unit#1 Shaun Featherstone (Frock n Robe) 7 - 24 May

The Red Shoes - Richard Of York Gave Battle In Vain 5 April - 21 June

- Unit#1 Megan Broadmeadow 5 April - 3 May

Under The Influence - UNIT(e) 2014 15 January - 15 March

- Unit#1 James Green 0 January - 21 June

- 2013

- Democracy Sandwich 21 November

- WJEC Foundation Excellence Exhibition and Awards 9 - 14 November

- Lost in Transit 19 October - 0 January

Offsite project at Cathays Library for MadeinRoath 2013 - MadeinRoath2013 17 - 24 October

The annual hyper-local festival - The John Gingell Award 17 August - 28 September

- Barnraising & Bunkers 8 May - 29 June

- There Will Be Words 13 - 28 March

Symposia/ Exhibition/ Projects

- 2012

- Recycled Cinema 10 - 24 November

- Brzeska`s Eagle 13 October - 0 January

- Chekhov`s Gun 29 September - 15 December

- Unit#1 Huw Andrews 10 - 24 August

- Unit#1 David Shepherd 14 - 28 July

- Unit#1: Rachel Calder 15 - 30 June

- The Autobiography of a Super-Tramp 6 June - 25 August

- Art Car Bootique 2012 15 April

Cardiff`s best annual car boot fair event at Chapter Arts Centre

- 2011

- g39`s Great Big Open Day 17 December

- GOLDEN ROD Adorned Log 28 October - 2 November

- CAMP 21 - 30 October

- Richard Higlett Welcome To Your World 1 - 15 October

- ¿AreWeNotDrawnOnwardToNewEra? 22 June - 2 July

The grand finale of the g39 project... - Portmanteau 30 April - 1 May

Offsite project at Halle 14, Leipzig, Germany - If.... Alistair Owen 16 March - 2 April

- Show One Of Each: Maia Conran 4 February - 12 March

- If.... Lulu Allison 12 - 29 January

- 2010

- The Last Days of The Empire 4 - 22 December

- On Collecting: Transactions in Contemporary Art 3 December

Symposium at Reardon Smith Lecture Theatre, National Museum Cardiff - Show One Of Each: Pascal-Michel Dubois 22 October - 27 November

I saw my destiny in the corner of my eyes - If.... Richard Cook 29 September - 16 October

- Bystanding 21 August - 25 September

Lauren Elizabeth Jury, Will Woon, Mark Folds - If.... Dawn Woolley 28 July - 14 August

- Unassembed Information: Towards an archive 8 - 24 July

With associated conference at NMW on 8 July 11-4 - If.... Candice Jacobs 7 - 24 July

- Awst & Walther: The Conversation 29 May - 3 July

- If.... Samuel Hasler: Block 4 - 22 May

- Short Cuts 27 March - 1 May

- If.... Heather Phillipson 24 February - 13 March

- If.... Lesley Guy 3 - 20 February

- 2009

- Richard Bevan 12 December - 30 January

Closed 20 December - 5 January - December Eleven 11 December

- Building Up Not Tearing Down 11 - 19 December

An off-site project at Tactile Bosch, Cardiff - If.... Rabab Ghazoul 18 November - 5 December

- Infernal Machine 10 October - 14 November

- Drawn In, Drawn Out, Drawn Round 1 - 12 October

An offsite exhibition at National Theatre Wales - If.... Hayley Lock 16 September - 3 October

- For Sale: Baby Shoes, Never Worn 8 August - 12 September

- Prop 5 - 22 August

An offsite exhibition at National Theatre Wales - The Golden Record 16 May - 20 June

- Jackie Chettur: 310 28 March - 2 May

- Helen Sear 31 January - 7 March

- Richard Bevan 12 December - 30 January

- 2008

- Simon Holly : The tipyn point 29 November - 17 January

- Rebecca Spooner: The White Stag 4 October - 1 November

- If You Build It They Will Come 9 July - 9 August

- Anna Barratt 17 May - 14 June

- Jennie Savage: A Million Moments 19 April - 5 May

Special arcade screening: Friday 18 April 8.00-9.15pm - Mike Murray: Building Blocks 5 April - 3 May

- Neil McNally: Death is colder than love 16 February - 15 March

- 2007

- 2006

- 2005

- 2004

- 2003

- 2002

- 2001

- 2000

- 1999

- 1998